-

Things to Do

-

Plan

-

About

Dutchess County is nestled in the heart of New York’s Hudson Valley, where chefs, bakers, vintners and more have access to some of the finest ingredients in the Northeast. In addition, the region’s history as an artist hub inspires all sorts of creators. Here, makers are made.

Cider dates back to the early days of colonial America, and made a huge revival within the last two decades. “The exciting growth of New York State’s cider industry has strong roots in the Hudson Valley’s 350 year history of commercial apple growing,” says Dutchess Tourism, Inc. President & CEO Melaine Rottkamp.

Though popular year-round, cider has a special place in the autumn season. As the leaves change and visitors travel from far and wide to pick-their-own apples fresh off the trees, this crisp, elegant beverage reaches new heights.

From August through October, apples reach their peak at local orchards. Experiencing fall harvest encourages the sampling of local craft ciders.

Related: Pick-Your-Own Apples, Pumpkins and More at These Dutchess Farms

Fishkill Farms in Hopewell Junction stands as a shining example of the Hudson Valley’s extraordinary apple-growing and cider-producing tradition. After studying at Cornell University—a national leader in apple breeding and variety research—Henry Morgenthau Jr. founded Fishkill Farms in 1913. He hosted both President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and served as FDR’s Secretary of the Treasury. Today, Fishkill Farms remains a community staple for pick-your-own produce, family activities and hard cider.

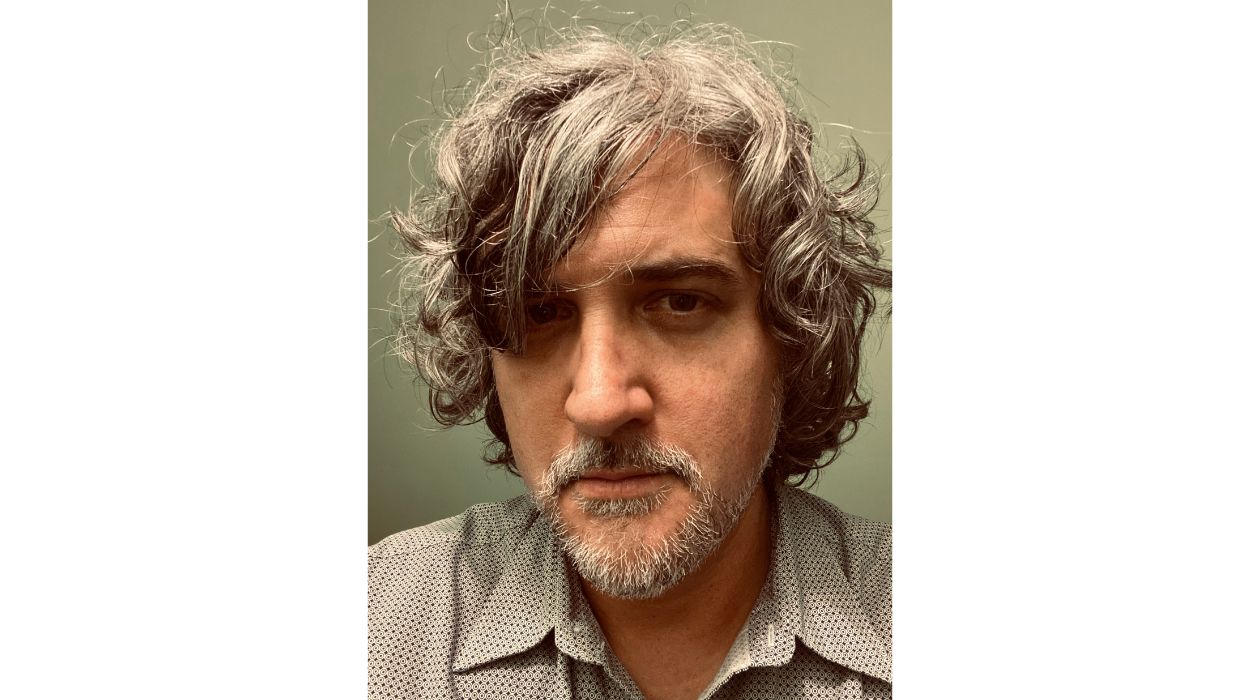

Treasury Cider at Fishkill Farms produces a variety of interesting tree-to-glass ciders. We spoke with head cider maker Chris Jackson to learn more about the ins and outs of his craft.

Chris Jackson works diligently with Fishkill Farms owner Joshua Morgenthau, Assistant Cider Maker Matia Hayden and the farmers at Fishkill Farms to craft tree-to-bottle ciders. The name "Treasury Cider" refers to Henry Morgenthau Jr.’s prestigious position, but goes deeper. Seeds planted span generations in an orchard—a treasury for future art. Each fall, the team selects the most flavorful varieties to ferment into extremely fine cider.

Most or all of these ciders are wild fermented, a process that reflects Dutchess County’s hyper-specific terroir. Jackson uses native indigenous yeast from the property, a technique also called spontaneous fermentation—meaning you can taste Fishkill Farms in every sip. “I'm a big fan of the native fermentation, it really tells you what your “space” tastes like,” Jackson remarks.

But before we delve into the specifics of what makes these ciders truly special, how did Jackson become the head cider maker at this historic orchard?

Well, it didn’t start where one would expect.

“I actually have a master's degree in Environmental Engineering…I did that for a number of years in Tampa. I’m also a musician,” he says.

After nearly a decade in the industry working as an engineer, he shifted his career toward the creative arts. “So at some point I left engineering and moved to Los Angeles to focus on music a little bit. I became an art director with a company that licenses art around Disney, Pixar and Star Wars. So that was a pretty radical move there. And then I began dating my wife, who was training to be a helicopter pilot here in the Hudson Valley at the time.”

In fact, he relocated to the Hudson Valley without a plan for where his career would go next. However, the region’s abundance of fall fruit captivated him. Admittedly, seeing so many apples in Dutchess County was a “cool novelty” for the Florida-raised Jackson. He’s always been a culinary-minded person, and even experimented with home brewing in the past.

One day, he and a buddy acquired a cider press. “We bought some apples and did it a few times, and I really took to it. I got comfortable enough to the point where I kept harassing Fishkill Farms to let me join [their team],” Jackson recalls.

It just so happened they were looking for an assistant cider maker a little over four years ago. A series of microburst storms reaped a ton of damage to the trees at Fishkill Farms.

“I showed up a short time—maybe two days after that, and they needed help. So I said, well, let me come help and we’ll see how it goes. That’s where the story begins,” Jackson says.

He became head cider maker within two years, and never takes for granted this incredible opportunity. Fishkill Farms cultivates many eco-certified apples, which grow with very little intrusion and pesticides. Jackson loves when visitors to the Treasury Cider bar and ask “where do you guys get your apple from?”

“From right here,” he responds, wearing a proud smile.

Related: How 10 Dutchess County Destinations Strive for Sustainability

All of their ciders begin in the orchard. The Dutchess County farm grows nearly 100 apple varieties, resulting in a myriad of flavors and cider styles. Quickly, the team harvests a slew of apple varieties and put them into bins and in the cooler for a while, as they are so focused on pick-your-own business through October.

So the apples come in, and they get sorted by hand as they go by conveyor belt into a machine. Then they go into burlap cloths between plastic plates, where a 100-year-old press press comes down and presses them. “That is pretty cool, and it works great. And Rohan Chamberlain is a very important part of the puzzle because he runs that for us,” Jackson remarks. “Our cidery itself shares a wall with the pressing room so we have a hose that runs right from the press.”

They always sulfite as minimally as possible at pressing, which helps keep things on track through the fermentation. For Jackson, the biggest element of this stage is “babysitting.” He and his crew monitor this every day or two. They check the specific gravity, which reveals exactly how much sugar is in the mix as well as the pH, which shows where the acid level is.

He’s always looking for the sugar to go completely away. Treasury Cider “ferments to dryness”—all of the sugar from the apples is out. The mixture cools to 50 degrees as it ferments, where it continues blending. It can take as quickly as two weeks, but will often remain in the tanks longer before being bottled. In fact, for aged ciders the entire process can last as long as six months.

At the time of bottling, Jackson adds sugar and pitches with a small amount of cultivated yeast. This bottle conditioning naturally carbonates the cider.

“We pitch additional yeast that is without a ton of personality, so to speak, because we're not looking for it to impart any [flavor or other characteristics]. We're just looking for it to go in and eat that sugar,” Jackson explains. “And once it's in a bottle, if it's eating that sugar, there's nowhere for that generated carbon dioxide to go; as opposed to when you're fermenting a big vat of juice it bubbles through the airlock. So, the bottle contains all of that carbon dioxide which eventually goes back into solution. That is your carbonation.”

He describes these bubbles as finer and creamier than those you’d find in a force carbonated cider. “I would say it’s a little more refined, like champagne vs soda.”

In addition, bottle conditioning includes something called the lees. This is sediment found at the bottom of the bottle, a result of that additional pitched yeast. Jackson encourages visitors not to fear the lees, but to embrace it. He swirls the bottle before opening, and the sediment brings a very interesting character to the cider.

So, what do these ciders taste like? Let’s start with their flagship, Homestead.

This semi-dry cider features a clean, crisp profile. Jackson explains that subtle honey notes come from the large amount of dessert fruit. It’s one of only two that are semi-dry, that’s the sweetest Treasury Ciders get. So, Homestead is an excellent place to start, a “gateway cider” as he puts it.

Homestead includes Cortlandt, Golden Delicious, Mcintosh and other more common varieties that are also available to pick at the Hudson Valley farm. Because of Fishkill Farms’ size and thriving pick-your-own business, Jackson is able to produce the most of this cider. He also uses Roxbury Russet and Ashmead’s Kernel apples, which bring beautiful bitter notes and tannins. There’s also an herbal, almost minty/menthol sensation which he attributes to the yeast.

“It’s really good to be honest. Sometimes I feel like I downplay Homestead because I love—as most people in this position probably do—very dry stuff, along with barrel aged and funky ciders,” Jackson admits. “Homestead is a little more accessible.”

It’s also backsweetened, which requires a few extra steps than the dry ciders. Sugar is added during the fermentation, so they have to remove the yeast via a complex filtration process. Otherwise, the yeast will simply eat whatever sugar that gets added, resulting in a dry cider. It stays cold in a bright tank, and gets force-carbonated by what is essentially a giant soda stream.

The other semi-dry cider found at Treasury Cider, Wild at Heart, is also backsweetened. He identifies this one as the staff favorite. Similar to Homestead, Wild at Heart showcases many dessert varieties like Idared, Jonagold and Pink Lady.

However, it’s got a very unique ingredient: Staghorn sumac. Jackson sources this red, fuzzy pine-cone-like ingredient from the farm. It happens to grow naturally on the Dutchess County property.

“We put in whole clusters of wild foraged sumac…the wood that is on there actually presents an interesting note too, it almost has a barrel quality in the background,” Jackson says. “I actually found a home in Hudson while just literally scouting around that had tons of it growing in the yard. I found the owner, and traded him cider for sumac.”

Wild at Heart tastes bright and citrusy, with notes of lemon and woodsy earth tones. The foraged sumac brings a hint of pink color to the cider, as well.

For Jackson, choosing a favorite is a difficult task. “It’s like picking a favorite child or a favorite Beatles song. I don’t want to have to answer that, but if I have to Burr Knot is where I go….and ‘Hello, Goodbye’.”

Burr Knot represents the funky, dry ciders that Jackson gravitates toward. It’s extremely dry and unfiltered, with a golden-brown color from the barrel-aging process. On the palate, he detects notes of orange creamsicle, caramel, eucalyptus, mint and vanilla, with a slight perceived sweetness but no sugar.

Burr Knot features a heavy dose of Hudson Valley heirloom apples, alongside bittersweet and crab apples (which provide a nicely tannic quality). He tends to like things a little bolder.

Some of the varieties in Burr Knot, like Harrison, Goldrush, Medaille D’or, Yarlington and Brown Snout are lesser known. Jackson mentions that Burr Knot may be the most complex cider they currently produce.

“I’m super lucky that 10+ years ago the owners saw where [the industry] was headed. We have a ton of varieties that [other cider makers] are really after. So that's great, and it's a nice nice position to be in.”

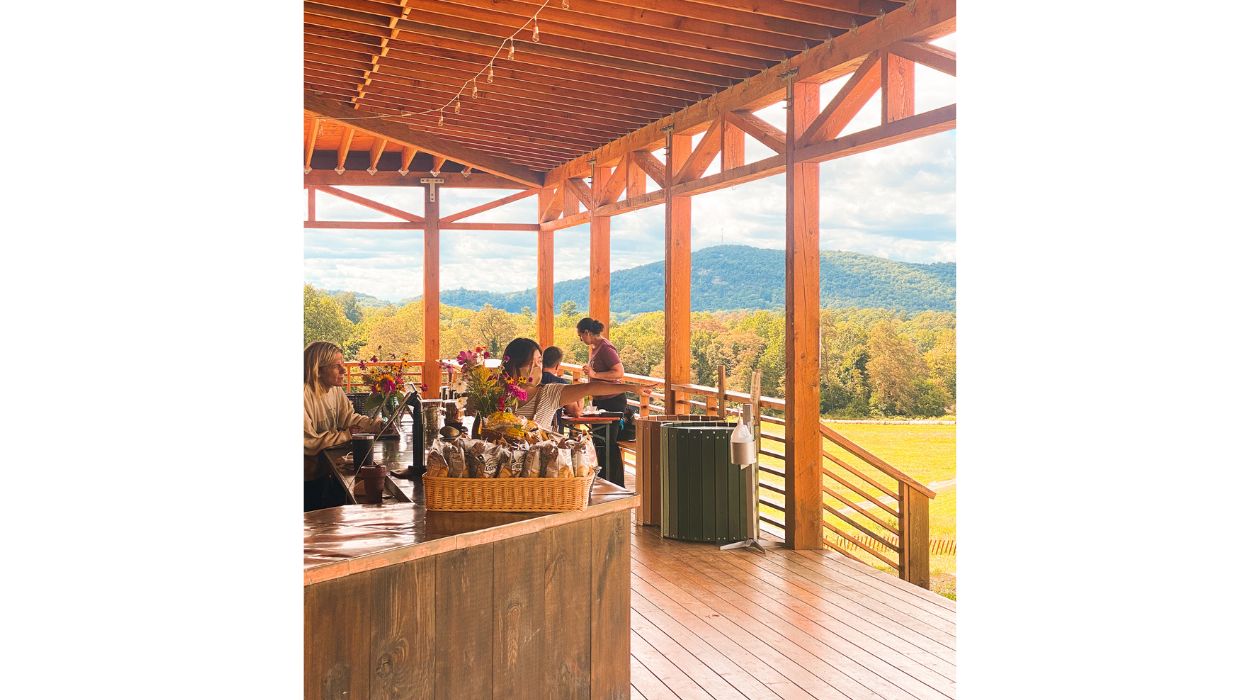

Visit the Cider Bar at Fishkill Farms to try these and many other unique craft sips. A grill provides plenty of food to pair with, and reservations can be made to include a small cheese and snacks plate.

In fact, Treasury Cider is a part of the Dutchess Tourism Taste Finder Craft Beverage Trail. This mobile passport that delivers perks at more than a dozen craft beverage hotspots across the county, spanning beer, wine, spirits, cider and mead. Passport check-ins at Treasury Cider get you a full tasting flight of ciders. Select a 1-day, 3-day, or 90-day pass and save up to 77%. Don’t forget to capture and share your experiences on social media using #CheersDutchess! To get your Taste Finder passport, click here.

Related: Use Your Dutchess Tourism Taste Finder Passport to Sip and Save in Style

Covid-19 Information

Our top priority is the safety, health, and wellbeing of our community, its residents and visitors.

Information for visitors & residents Information & Resources